Record renewables in the UK? Not good enough!

It’s all over the news recently: The UK produced a record amount of renewable energy in 2022.

This is GREAT news and definitely something the UK should be proud of, but it does not indicate that the country is entirely on track to meet its net-zero goals by 2050.

The UK is still playing catch-up in decarbonising its gas-based heating infrastructure, its solar power yields are comparably low, and there is a literal gridlock when it comes to connecting new renewable ventures onto the mains.

And quite frankly, record renewables can be a misleading figure.

Let’s take a dive

Contents

- UK renewables in 2023

- A brief history of UK renewables

- Renewable electricity is NOT the best metric

- UK heating is not being considered

- Renewable energy is not always low-carbon

- Renewable adoption in context

- Gridlock in the UK grid

- Conclusion

- External Resources

UK renewables in 2023

The latest official figures indicate that the UK produced nearly 40% of its electricity from renewables in 2022.

This was composed of:

- 26.8% Wind energy

- 5.2% Biomass (mainly Drax power station)

- 4.4% Solar energy

- 1.8% Hydropower (including tidal energy and PSH)

This percentage increase has been growing year-on-year as the UK is taking its climate commitments ever so seriously, coming from barely any renewable electricity generation back in the naughties…

A brief history of UK renewables

In 1991, the world’s primary environmental concern was the depletion of the Ozone layer. The Kyoto Protocol hadn’t been signed, and the UK only produced 2% of its electricity from renewables.

Climate change rapidly became mainstream over the next two decades, and by 2010, the UK was producing almost 10% of its electricity from renewables.

Fast forward twelve years, and the UK produced 40% of its electricity from renewables in 2022, which marked the first year in which renewables finally overtook natural gas as the main source of electricity.

This shows how the UK has come leaps and bounds in a short time, particularly by taking advantage of its plentiful wind resources. There are, however, some issues with this.

Renewable electricity is NOT the best metric

It is often too easy to hand-pick figures that best support a narrative, i.e. greenwashing, without them necessarily being the most appropriate figures to represent the main issue, in this case, climate change.

Decarbonisation is more than just switching to renewables for electricity production. These two points are often overlooked:

- Heating applications are actually the UK’s principal energy consumer (i.e. using gas boilers to heat water).

- Renewable energy does not always mean low carbon, e.g. biomass energy, and it does not include nuclear energy.

UK heating is not being considered

Nearly half of all the energy consumed in the UK is for heating, a much larger share than the energy used to produce electricity or move transportation around (with petrol/diesel).

Some of this heating is for industrial purposes, but 57% goes towards heating the air and water within buildings. And of this 57%, three-quarters is powered by natural gas boilers, which are direct carbon emitters and the antithesis of clean, renewable business energy.

Doing the maths indicated that approximately 20% of all energy used in the UK comes from burning gas for heating, regardless of the number of renewables used to produce electricity. This is a source of a lot of emissions.

Efforts to decarbonise heating are focused on improving building insulation, installing electric heat pumps and replacing gas boilers with renewable (yet not so low-carbon) biomass boilers.

Yet much remains undone!

Renewable energy is not always low-carbon

This is somewhat a source of controversy in the endless debate about whether or not biomass energy is indeed net zero or just a well-manipulated case of greenwashing.

This topic is particularly hot in the UK because over 5% of the renewable output in 2022 came from burning wood pellets at Drax, which claims its process will become carbon-negative when it incorporates carbon capture and storage (CCUS) over the coming decade.

However, a recent investigation by The Guardian found that Drax’s global supply chain of wood pellets often did not meet the reported standards and was even the source of some questionable wood harvesting of primary forests in British Columbia, Canada.

Otherwise, burning wood is hard to imagine as an ideal decarbonisation solution. Burning wood returns any carbon captured by growing forests straight back into the atmosphere.

So while biomass is included and eligible to receive many government subsidies, low-carbon energy such as nuclear power is not categorized as renewable, even though it plays a primary role in global decarbonisation, particularly in countries like China that require colossal amounts of electricity.

Renewable adoption in context

There is, however, no such thing as a perfect country, so it’s important to compare how renewable adoption has changed in the UK compared to other similar economies, such as Germany.

We compared the adoption of clean energy and found out that the UK has generally faired well, particularly in the adoption of offshore wind energy, in which the UK is clearly a global leader.

This has helped the UK virtually phase out coal by 2022, something other countries like the Netherlands have largely been unable to do.

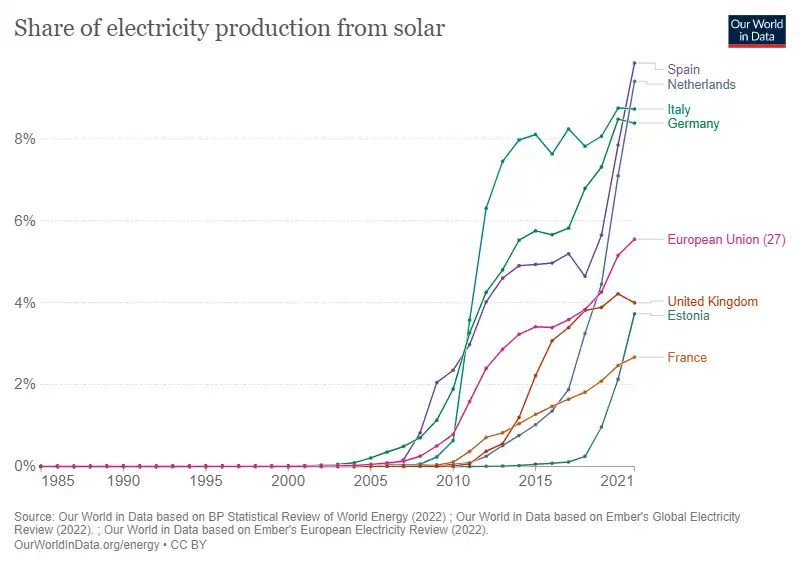

However, the UK is lagging behind on solar power, while the Netherlands and Germany have been experiencing exponential adoption of commercial solar power, largely from feed-in-tariff schemes.

Otherwise, hydropower is barely growing in the UK, while geothermal is coming back via small-scale Cornish deep geothermal.

So, the UK is comparatively not in such a bad place, particularly when considering it just went through the energy crisis when business electricity rates and commercial gas prices soared.

But there may just be something simple holding us back…

Gridlock in the UK grid

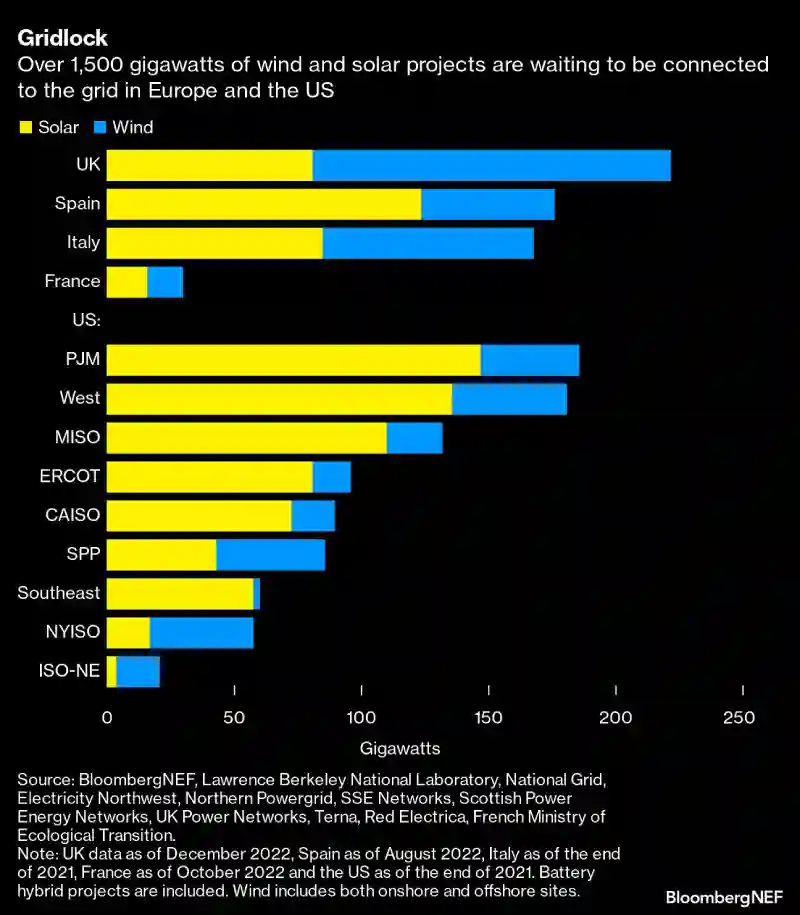

As is clear from the chart above, the UK is clearly a leader in making renewable ventures wait in line, forming a literal gridlock when it comes to the necessary grid connections.

The UK currently has 200GW of renewable energy (mainly offshore wind), 4x the current capacity, in the national grid’s waitlist. Without this public work, renewable companies cannot guarantee they will sell energy to business energy suppliers when they finish, potentially putting them in bankruptcy!

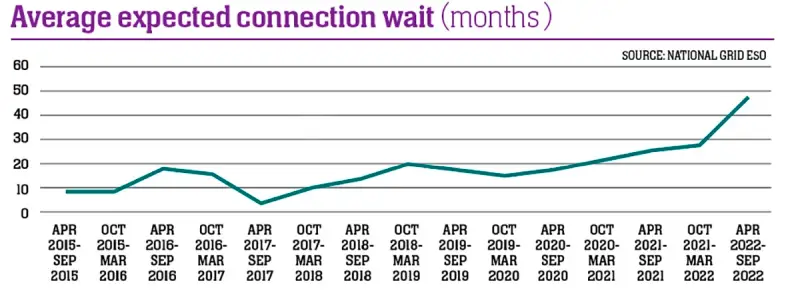

In 2022, the average wait time was approaching 4 years, yet some are reporting a waitlist of ten years or longer. To alleviate this problem, the UK government has recently introduced the TEC amnesty.

Now, building the infrastructure for a new offshore wind farm is not cheap or easy, even for a small and densely populated country like the UK, but it is essential. It’s like having the cars but not the wheels.

For example, energy firm Centrica has a database of over 400 sites that are technically ideal for building renewables, yet 90% of them are unfeasible due to the waiting time for a connection being too long!

Conclusion

Sure, the UK is breaking renewable records, which is encouraging. It helps combat climate doom and is a step in the right direction.

However, measuring renewable electricity production is NOT the full picture. The UK still needs to press the gas on heating decarbonisation, give biomass a long, hard look, and consider all low-carbon energy in its releases, even when nuclear is sometimes not the most popular.

And the gridlock in grid connection is just the cherry on the cake, as the UK government is in charge of ensuring the network is ready to support the efforts of renewable ventures acting with urgency.

Twenty-seven years remain before the net-zero deadline, and decarbonising renewables only is not going to do the trick!